Over the next few minutes, you’ll discover seven surprising facts about dendrites, how they shape neural signaling, and how your nervous system repairs damaged connections through plasticity, glial support, and molecular signaling; you’ll learn what affects signal integration, why dendritic structure matters for cognition, and how emerging research informs therapies you can expect in the future.

Key Takeaways:

- Dendrites perform nonlinear integration and can generate local dendritic spikes that shape neuronal output.

- Backpropagating action potentials into dendrites influence synaptic strength and timing-dependent plasticity.

- Dendritic spines undergo rapid structural plasticity-formation, enlargement, and pruning-underlying learning and memory.

- Dendrites contain local protein synthesis and compartmentalized calcium signaling for independent, rapid responses.

- CNS dendrite regeneration is limited; functional recovery depends on dendritic remodeling, neurotrophic factors (e.g., BDNF), and circuit reorganization.

- Microglia and astrocytes clear debris and release signals that guide dendritic repair and synaptic reformation after injury.

- Dendritic dysfunction is implicated in disorders (Alzheimer’s, autism, epilepsy), making synaptic and dendritic restoration therapeutic targets.

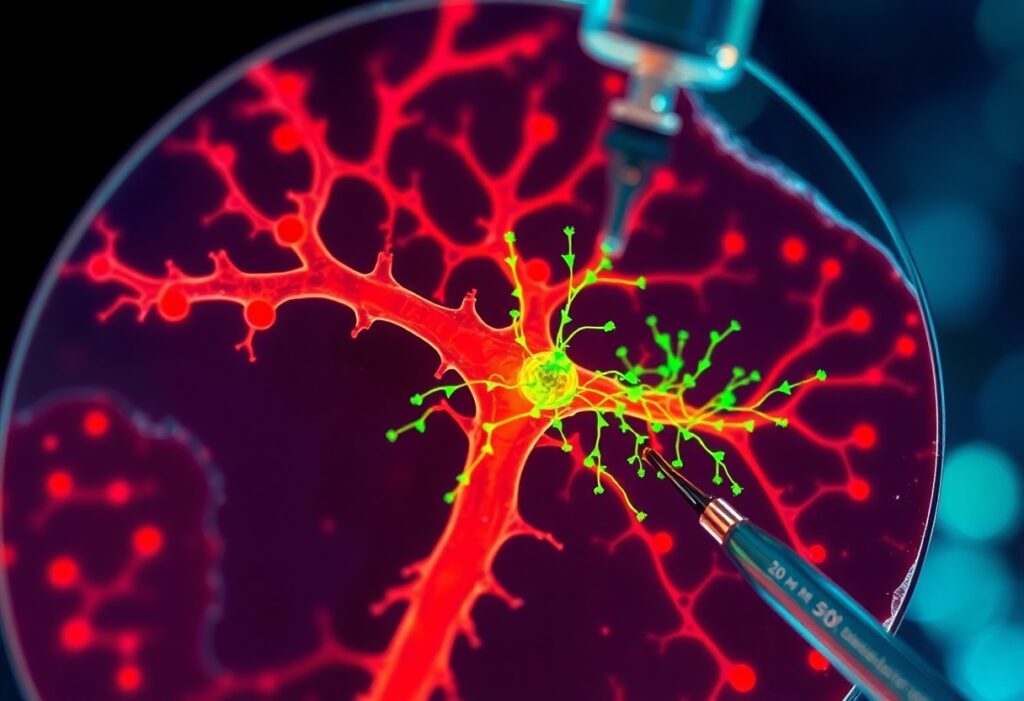

What Are Dendrites?

You see dendrites as the neuron’s input arbor: highly branched processes that span tens to hundreds of micrometers and host up to ~10,000 synapses, many on spines at densities near 1 spine/µm. Their spatial layout and spine distribution let your neuron segregate feedforward, feedback, and modulatory inputs, so that where a synapse lands matters as much as its strength when determining how signals combine and influence firing.

Structure and Function

Structurally, dendrites pair a cable-like shaft of microtubules with actin-rich spines that house AMPA/NMDA receptors; you’ll find voltage-gated Na+, Ca2+ and K+ channels distributed along branches to shape local excitability. Functionally, this architecture supports compartmentalized signaling and local protein synthesis in dendritic shafts and spines, enabling input-specific plasticity and rapid remodeling in response to activity or neuromodulators.

Role in Neural Signaling

Dendrites perform nonlinear integration: backpropagating action potentials attenuate with distance yet interact with synaptic currents to produce local dendritic spikes (NMDA-, Ca2+-, or Na+-mediated) that can amplify clustered inputs. You rely on these mechanisms for coincidence detection within tens of milliseconds and for gating spike-timing-dependent plasticity, so timing, location, and synchrony determine whether inputs merely summate or trigger regenerative events.

For example, in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells, activating a handful of nearby spines (roughly 5-20) within a short window (on the order of 5-20 ms) can evoke a branch-specific NMDA spike that generates a large local Ca2+ transient, biases somatic output, and selectively potentiates those synapses-demonstrating how spatial clustering and precise timing let your dendrites perform powerful, input-specific computations.

Shocking Fact #1: Dendrite Growth and Learning

Activity-driven spine remodeling

When you practice a new skill, dendritic spines proliferate rapidly-mouse motor cortex shows 10-30% new spines within 24-48 hours of training. Synaptic potentiation triggers actin-driven spine enlargement in minutes, and BDNF signaling promotes branching over days. Studies found roughly 30-50% of newly formed spines persist after consolidation, linking structural change to memory retention; sleep and repeated rehearsal determine which spines stabilize versus which regress.

Shocking Fact #2: Dendritic Spine Changes with Experience

Experience-driven spine remodeling

If you learn a new motor task, your neurons add new spines rapidly: in mouse motor cortex, skilled reaching produces ~10-20% new spines within days, and about half of those persist for weeks, correlating with retained skill; in vivo two-photon imaging even shows some spines form within minutes after stimulation while others retract, so your synaptic landscape is continuously rewritten by practice, stress, and sensory input.

Shocking Fact #3: Impact of Stress on Dendrites

Stress reshapes circuits

Chronic stress remodels dendrites differently across brain regions. In rodent models, 21-28 days of chronic restraint or unpredictable stress causes ~20% retraction of CA3 apical dendritic length and up to 40% increased branching in the basolateral amygdala. Elevated glucocorticoids and glutamate drive these changes, and in many studies dendritic atrophy in hippocampus reverses after weeks of recovery or antidepressant treatment. That means when you undergo prolonged stress your memory-related circuits can weaken while fear circuits strengthen, altering behavior and cognition.

Dendrite Repair Mechanisms

During repair you observe microglia and astrocytes clear debris within 24-72 hours while local protein synthesis and actin remodeling rebuild spines; BDNF and IGF‑1 signaling rise over days to weeks to guide new branches. Peripheral neurons regenerate more readily than central ones, so functional recovery often depends on local rewiring and synaptic reinnervation measured over weeks to months.

Neuroplasticity and Recovery

Synaptic plasticity drives much of the functional comeback: you get rapid spine formation within hours after activity or injury, LTP/LTD sculpt which connections persist, and homeostatic scaling prevents network instability. Clinical tools-task-specific practice, constraint therapy, and neuromodulation like TMS-can produce measurable gains in 2-12 weeks by increasing stable spine retention and reorganizing cortical maps.

Factors Influencing Repair

Your recovery is shaped by biological and lifestyle variables; key modulators include:

- Age – younger brains show higher spine turnover and faster regrowth.

- Inflammation – microglial activation within 24-72 hours can either support cleanup or hinder regrowth, depending on magnitude.

- Rehabilitation – task-specific practice improves synaptic reinnervation in animal models.

- Sleep and metabolism – <7 hours sleep or poor glycemic control reduces BDNF and plasticity.

After, prioritize interventions that reduce chronic inflammation and increase activity-dependent signaling to bias repair toward functional outcomes.

You can target specific factors to accelerate repair:

- Exercise – 30-45 minutes of moderate aerobic activity most days elevates circulating BDNF and supports spine formation.

- Sleep hygiene – consistent 7-9 hour schedules improve spine consolidation and retention.

- Pharmacologic windows – in animal studies SSRIs and neuromodulators have reopened plasticity periods, enabling retraining.

- Nutrition – omega‑3s and adequate protein provide building blocks for membrane and cytoskeletal repair.

After, combine behavioral, medical, and lifestyle strategies with clinician-guided rehab to maximize dendritic recovery.

Implications for Neurological Health

Clinical impact and recovery

In Alzheimer’s, postmortem studies report 25-50% dendritic spine loss in hippocampus and cortex; after ischemic stroke you see dendritic beading within minutes and peri‑infarct spine density often falls over 50% within 24 hours. Chronic stress reduces prefrontal dendritic complexity by ~20-30% in rodents, while rodent motor training boosts new spine formation by ~20% within days. You can leverage interventions-exercise (1 year aerobic training increased hippocampal volume ~2% in older adults) and BDNF‑promoting rehab-to partly restore your brain’s structure and function.

Conclusion

Considering all points, you can see how dendrites shape neural signaling, adapt through plasticity, and support recovery after injury; understanding their branching, synaptic integration, and repair mechanisms empowers you to appreciate interventions that enhance neural resilience and guide research or therapies aimed at restoring function.

FAQ

Q: What are dendrites and what role do they play in neural signaling?

A: Dendrites are branched neuronal processes that receive synaptic inputs from other neurons. They integrate excitatory and inhibitory signals through thousands of synapses, convert chemical neurotransmission into local electrical events, and help determine whether the neuron fires an action potential by shaping spatial and temporal summation of inputs.

Q: How do dendrites actively influence electrical signaling rather than just passively carrying inputs?

A: Dendrites contain voltage-gated ion channels (e.g., Na+, Ca2+, K+) and can generate local regenerative events such as dendritic spikes and backpropagating action potentials. These active properties amplify, filter, or transform incoming signals, enable compartmentalized processing, and allow synapses at different dendritic locations to have distinct impacts on neuronal output.

Q: What are dendritic spines and how do they relate to learning and memory?

A: Dendritic spines are small protrusions that host most excitatory synapses in the brain. Spine size and shape correlate with synaptic strength; long-term potentiation (LTP) and depression (LTD) produce structural and molecular changes in spines. Spine formation, elimination, and stabilization underlie experience-dependent circuit remodeling that supports learning and memory.

Q: Do dendrites make proteins locally, and why does that matter?

A: Yes. Dendrites contain ribosomes, mRNAs, and local translation machinery that produce proteins near synapses on demand. Local protein synthesis enables rapid, synapse-specific changes in receptor composition, cytoskeleton, and signaling molecules that are required for long-lasting synaptic plasticity and structural remodeling without waiting for somatic protein delivery.

Q: Can dendrites regenerate after injury, and how does this compare to axon regeneration?

A: Dendritic regeneration is limited but possible; peripheral neurons and some CNS neurons can remodel dendritic arbors after injury, while widespread mature CNS dendrite repair is restricted by inhibitory molecules, inflammation, and glial scarring. Unlike axon regeneration research, dendritic regrowth involves restoring complex branching and synaptic patterns and is influenced heavily by local circuit activity and glial responses.

Q: What biological mechanisms help the body repair dendritic damage?

A: Repair mechanisms include microglial clearance of debris, astrocyte-mediated metabolic and trophic support, release of growth factors (e.g., BDNF, CNTF), activation of intrinsic growth programs (growth-associated proteins, cytoskeletal remodeling), and activity-dependent synaptic reorganization driven by rehabilitation or sensory experience. Balanced inflammation and timely trophic signaling are important for productive remodeling.

Q: What therapeutic strategies are being explored to enhance dendritic repair and circuit recovery?

A: Approaches under investigation include delivery or upregulation of neurotrophic factors (BDNF, NT-3), modulation of inhibitory pathways (anti-Nogo, RhoA/ROCK inhibitors), neuromodulation and patterned electrical stimulation to promote activity-dependent plasticity, small molecules that boost intrinsic growth programs, cell-based therapies to provide support or replace lost cells, and targeted rehabilitation protocols that encourage adaptive dendritic remodeling and synapse formation.