You may be eating well and sleeping enough yet still feel drained; mitochondrial dysfunction can silently sap your cellular energy. This post outlines seven often-overlooked mitochondrial reasons-oxidative stress, nutrient shortfalls, toxin exposure, hormonal imbalances, chronic inflammation, impaired mitophagy, and genetic variants-that blunt ATP production and keep you tired, and it offers evidence-based strategies to assess and support your mitochondria so you can restore reliable energy.

Key Takeaways:

- Mitochondrial dysfunction lowers ATP production so cells can’t turn food and oxygen into usable energy, even with good sleep and diet.

- Deficiencies in CoQ10, B vitamins, magnesium, iron and other cofactors impair the electron transport chain and energy generation.

- Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress damage mitochondrial membranes and DNA, reducing efficiency and increasing fatigue.

- Environmental toxins and certain medications (heavy metals, pesticides, some statins/antibiotics) inhibit mitochondrial enzymes and raise reactive oxygen species.

- Poor mitochondrial biogenesis or defective mitophagy from sedentary behavior, aging, or hormonal imbalances leads to fewer or dysfunctional mitochondria.

- Circadian disruption and fragmented sleep architecture disturb mitochondrial metabolism and daytime energy despite adequate hours asleep.

- Gut dysbiosis, malabsorption or genetic variants can limit nutrient availability or directly impair mitochondrial function.

Mitochondrial Function and Energy Production

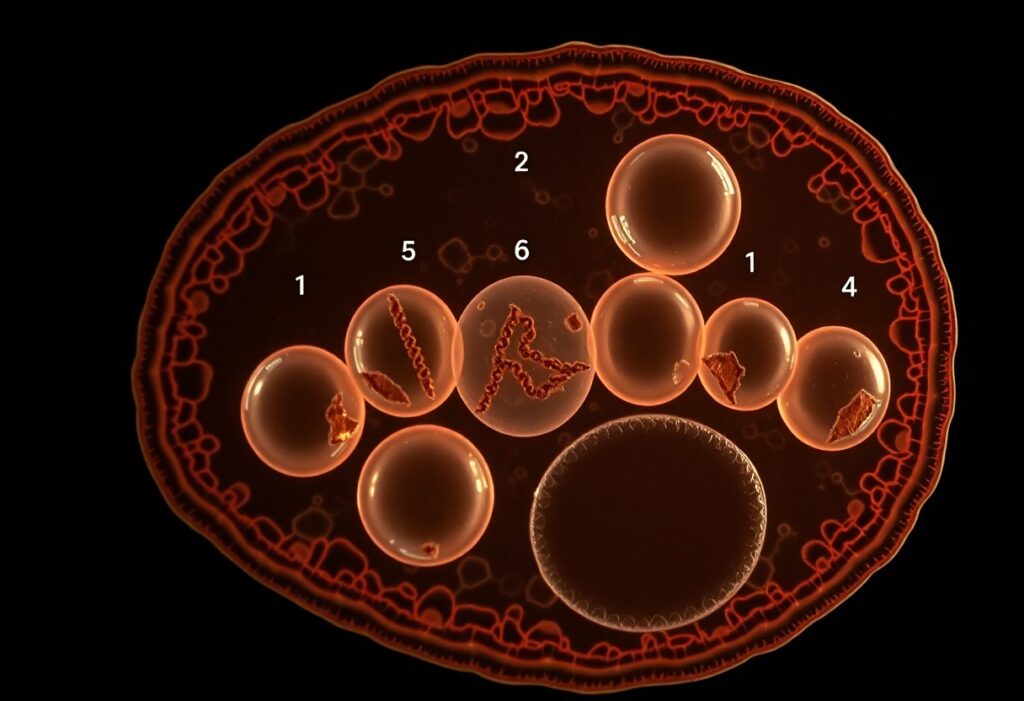

Inside your cells, mitochondria generate roughly 90% of usable ATP by running glycolysis-derived pyruvate through the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation, yielding about 30-32 ATP per glucose molecule; when any step-from substrate supply to the electron transport chain- falters, high-demand tissues like brain and muscle (which contain hundreds to thousands of mitochondria per cell) lose function first.

The Role of Mitochondria in Cellular Metabolism

Mitochondria do more than make ATP: they perform beta-oxidation of fatty acids, synthesize key metabolites, buffer calcium, initiate apoptosis, and enable steroidogenesis; your mitochondrial genome (~16,569 base pairs encoding 13 ETC proteins) and copy number affect how flexibly you switch between fuels and how resilient your cells are to metabolic stress.

Key Processes Affecting Energy Levels

Substrate availability (glucose, fatty acids), oxygen delivery, intact electron transport chain complexes, and healthy mitochondrial dynamics-fusion, fission, and mitophagy-set your cellular energy baseline; lifestyle changes like endurance training can increase mitochondrial content by roughly 20-50%, while deficiencies in B‑vitamins, CoQ10, iron, or chronic hypoxia lower ATP output.

At the molecular level, Complex I or IV impairments, mtDNA mutations/deletions, and cardiolipin oxidation reduce proton motive force and boost ROS production, directly cutting ATP synthesis; aging-related declines in mitophagy and exposures (certain antibiotics, statins in susceptible individuals) let dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate, which is why you may feel persistent fatigue despite adequate sleep and nutrition.

Nutritional Gaps Impacting Mitochondria

Micronutrient shortfalls directly reduce mitochondrial ATP production and raise oxidative stress, so you can eat “healthy” yet still functionally starve your cells. Deficiencies in CoQ10, B-vitamins, magnesium, iron, selenium, omega‑3s and vitamin D each impair electron transport, antioxidant defense or membrane integrity. In clinical screens, low ferritin (<50 ng/mL), B12 (<300 pg/mL) or vitamin D (<30 ng/mL) often correlate with persistent fatigue despite adequate calories.

Essential Nutrients for Optimal Function

You need specific cofactors: B1/B2/B3/B5 build NAD/FAD carriers, B12 supports mitochondrial DNA maintenance, magnesium stabilizes ATP (RDA ~310-420 mg), iron forms cytochromes (RDA 8 mg men/18 mg premenopausal women), selenium enables selenoprotein antioxidants, and CoQ10 shuttles electrons-found in organ meats, oily fish, nuts, leafy greens and fortified foods.

Common Dietary Mistakes

Severe calorie restriction (e.g., 1,200 kcal/day), ultra‑processed diets, low‑fat trends and exclusionary eating (vegan without B12/iron planning) strip mitochondrial substrates and cofactors; many people assume fortified foods replace whole‑food cofactors but miss magnesium, selenium and bioavailable iron needed for ETC enzymes.

In practice, athletes on carb‑heavy low‑fat plans often show low carnitine and omega‑3 status, while older adults on PPIs or metformin develop B12 insufficiency that impairs mitochondrial repair; statin users frequently report fatigue linked to reduced CoQ10 synthesis. You should test ferritin, B12 and vitamin D when fatigue persists, prioritize whole‑food sources (sardines, liver, spinach, nuts) and consider targeted supplementation-CoQ10 trials commonly use 100-300 mg/day and magnesium 200-400 mg/day under clinician guidance-to restore mitochondrial function.

Environmental Factors Affecting Energy Levels

Pollutants, indoor mold, and chronic low‑level exposures to heavy metals and pesticides blunt mitochondrial efficiency by increasing reactive oxygen species and impairing the electron transport chain; air pollution studies link PM2.5 exposure to decreased mitochondrial DNA copy number and elevated 8‑OHdG. Any cumulative exposure over months to years compounds ATP deficits and can leave you chronically fatigued despite good sleep and diet.

- Air pollution (PM2.5, NO2)

- Heavy metals (lead, mercury)

- Pesticides & industrial solvents

- Mold and mycotoxins

- Household chemicals and endocrine disruptors (BPA, phthalates)

Toxins and Their Impact on Mitochondria

Pesticides, solvents, and heavy metals directly target mitochondrial enzymes and membranes: mercury and lead disrupt thiol‑dependent enzymes, certain organophosphates inhibit complexes I/III, and mycotoxins like ochratoxin A lower mitochondrial membrane potential. You may see rises in oxidative markers (8‑OHdG, lipid peroxides) and reduced ATP output after repeated low‑level exposure, which explains unexplained fatigue in people without clear lifestyle deficits.

The Importance of Air Quality

Outdoor and indoor air both matter because PM2.5 and nitrogen oxides penetrate cells and trigger mitochondrial damage; the WHO now recommends an annual PM2.5 limit of 5 µg/m3, yet many urban and indoor settings routinely exceed that, increasing systemic oxidative stress and lowering mitochondrial DNA copy number in blood. You’ll notice energy drops when exposure is chronic, even if other health markers appear normal.

Mitigation steps you can take include using a true HEPA filter (captures ~99.97% of 0.3 µm particles), eliminating indoor combustion sources, testing for radon, and improving ventilation; targeted actions-like replacing gas stoves with electric or running a HEPA unit during high‑pollution days-have measurable effects on indoor PM and on biomarkers of inflammation, helping restore mitochondrial function and energy over weeks to months.

Stress and its Impact on Mitochondrial Health

Chronic psychological stress floods your system with glucocorticoids and catecholamines, which elevate reactive oxygen species and impair mitochondrial dynamics – fusion, fission and biogenesis. You may see reduced expression of PGC-1α (the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis), decreased ATP output, and increased mtDNA damage in stressed individuals and animal models, linking persistent stress directly to poorer cellular energy production and greater fatigue.

The Connection Between Stress and Energy Depletion

When you remain stressed, your body shifts toward anaerobic metabolism and inflammation, lowering mitochondrial ATP contribution; studies report impaired mitochondrial respiration and higher oxidative markers in chronically stressed cohorts such as long-term caregivers. Cortisol-mediated suppression of PGC-1α and damage to electron transport chain complexes I and III both cut ATP generation, which often shows up as daytime exhaustion despite adequate sleep and nutrition.

Strategies for Managing Stress

Targeted interventions restore mitochondrial resilience: daily 10-20 minute diaphragmatic breathing or HRV biofeedback lowers sympathetic drive, resistance training 2-3 times weekly boosts PGC-1α and mitochondrial density, and consistent 7-9 hours of sleep supports mitophagy. You should also prioritize social support and, when needed, evidence-based psychotherapy (CBT) to reduce HPA-axis activation and downstream mitochondrial harm.

To implement this, try a simple protocol: 10 minutes morning paced breathing (6 breaths/min), three 30-45 minute resistance sessions per week, and a wind-down routine to secure 7-9 hours of sleep. Add omega‑3-rich meals and limit stimulants after 2 pm to blunt evening cortisol. If fatigue persists despite these steps, pursue biomarker testing (hs-CRP, fasting cortisol, mtDNA damage assays) and consult a clinician for tailored interventions.

Sleep Quality and Mitochondrial Efficiency

Poor sleep fragmentation and reduced deep sleep blunt your mitochondrial ATP output by impairing mitophagy and biogenesis pathways like PGC‑1α-driven signaling. Adults need roughly 7-9 hours; chronic short or disrupted sleep correlates with lower mitochondrial respiration and higher oxidative markers in muscle and brain tissue. If you’re getting enough hours but waking often or losing slow‑wave sleep, your cells aren’t completing the overnight repair that restores energy reserves.

Sleep Cycles and Their Effect on Energy

Slow‑wave (N3) sleep – roughly 13-23% of total sleep in healthy adults – is when mitophagy and metabolic cleanup peak, while REM (about 20-25%) supports synaptic remodeling and neurotransmitter balance that influence perceived energy. When you truncate deep or REM stages (for example, by alcohol, late caffeine, or shift work), mitochondrial turnover drops and you’ll notice lower daytime stamina, impaired glucose handling, and slower recovery after exercise.

Improving Sleep for Better Mitochondrial Function

You can boost mitochondrial function by stabilizing circadian cues: keep a consistent wake time, aim for 7-9 hours, get 20-30 minutes of bright morning light, dim evening lighting 60-90 minutes before bed, and avoid caffeine within 6 hours of sleep. Also maintain a cool bedroom (around 60-67°F) and limit alcohol near bedtime – these measures increase slow‑wave sleep and support nightly mitochondrial repair.

For actionable steps, set a fixed wake time and expose yourself to outdoor light within 30 minutes of waking for at least 15-20 minutes, stop screens and bright LEDs an hour before bed, and schedule vigorous exercise earlier than 3-4 hours before sleep. If insomnia persists, track polysomnography or use actigraphy for 7-14 nights to identify stage fragmentation; targeted interventions (CBT‑I, melatonin timing of 0.5-1 mg at specific clock times) can restore sleep architecture and improve mitochondrial markers over weeks.

Physical Activity and Mitochondrial Optimization

When you prioritize targeted movement, you directly influence mitochondrial signaling pathways-boosting PGC-1α activity, enhancing ATP output, improving oxidative enzyme levels, and increasing mitophagy so damaged mitochondria are cleared and replaced with fitter organelles.

The Benefits of Regular Exercise

Regular training raises mitochondrial biogenesis and efficiency-studies report 20-40% increases in oxidative enzymes with sustained programs-so you gain greater ATP production, improved VO2max, better glucose regulation, and lower oxidative load that together reduce daytime fatigue.

Types of Exercise That Boost Mitochondrial Health

Endurance sessions (30-60 min, 3-5x/week) expand mitochondrial networks; HIIT (≤30 min, 2-3x/week) rapidly improves respiratory chain function; resistance training (2-3x/week) preserves mitochondrial quality in fast-twitch fibers; combining these modes yields the widest functional gains.

- Endurance: long steady-state work to increase mitochondrial number and capillaries.

- HIIT: short, intense bursts that upregulate oxidative enzymes and efficiency.

- Resistance: supports mitochondrial quality through muscle remodeling.

- Mixed programming: synergy between density and functional improvements.

- Knowing how to periodize these modalities across the week prevents overtraining and maximizes adaptation.

| Endurance | Increases mitochondrial density and capillary supply (30-60 min, 3-5x/wk) |

| HIIT | Improves respiratory chain efficiency and enzyme activity (≤30 min, 2-3x/wk) |

| Resistance | Enhances mitochondrial quality in fast-twitch fibers (2-3x/wk) |

| Tempo/Threshold | Raises oxidative threshold and sustained ATP production (20-40 min sessions) |

| Active Recovery | Promotes mitophagy and reduces oxidative stress (low-intensity movement) |

Alternating intensities triggers complementary molecular pathways: AMPK activation during low-energy states and PGC-1α induction post-exercise drive biogenesis, while moderate activity promotes mitophagy to clear dysfunctional mitochondria; for instance, HIIT protocols often show measurable mitochondrial marker improvements within 4-8 weeks, and combining resistance work helps retain function as you age.

- Schedule 2 HIIT sessions, 2 steady-state cardio sessions, and 2 resistance sessions weekly for balanced stimulus.

- Prioritize protein (1.2-1.6 g/kg/day) and sleep to support mitochondrial repair after training.

- Track performance metrics (power, pace, perceived exertion) to spot early fatigue and adjust load.

- Cycle intensity every 4-6 weeks to push adaptations while allowing recovery.

- Knowing how to adjust frequency and intensity based on your recovery ensures sustainable mitochondrial gains.

| Monday | HIIT (20 min) + mobility |

| Tuesday | Resistance training (45 min) |

| Wednesday | Steady-state cardio (40 min) |

| Thursday | Resistance or active recovery (light movement) |

| Friday | Steady-state or HIIT depending on recovery |

Final Words

Upon reflecting, you should consider how mitochondrial efficiency, genetic predispositions, toxin exposure, micronutrient shortfalls, sleep architecture, chronic inflammation, and medication effects can sap your energy even when you sleep and eat “right”. Assessing these factors with targeted testing and interventions can help restore cellular ATP production and improve your stamina; consult a clinician to tailor strategies to your biology.

FAQ

Q: How can mitochondrial DNA variants make you feel tired even when you sleep and eat “right”?

A: mtDNA heteroplasmy and inherited variants can reduce the efficiency of the electron transport chain, producing less ATP and more reactive oxygen species (ROS). Symptoms often include persistent fatigue, exercise intolerance, and slower recovery. Diagnosis requires specialized testing (mtDNA sequencing or muscle biopsy in some cases). Management focuses on symptom monitoring, personalized nutrition, targeted supplements (e.g., CoQ10, specific B vitamins after testing), graded exercise programs, and avoiding mitochondrial toxins; genetic counseling may be recommended for inherited conditions.

Q: Why does impaired mitophagy leave me exhausted despite good sleep and nutrition?

A: Mitophagy is the process that clears damaged mitochondria; when it’s impaired, dysfunctional mitochondria accumulate, lowering cellular ATP and increasing oxidative stress. This leads to sluggishness, brain fog, and poor stamina. Causes include aging, genetic factors, chronic inflammation, and some medications. Interventions that may help restore mitophagy include intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating patterns, specific exercise modalities (interval and resistance training), and emerging therapies under clinician guidance; research-backed supplements like nicotinamide precursors can support mitochondrial turnover but should be used with medical supervision.

Q: Can oxidative stress still sap my energy even if my diet is balanced?

A: Yes. Excess ROS production from mitochondria or insufficient antioxidant defenses (glutathione, vitamin C, vitamin E, selenium) damages mitochondrial membranes and enzymes, reducing ATP output. Contributing factors include environmental pollutants, high-intensity exercise without recovery, infections, and metabolic dysregulation. Testing can include markers of oxidative damage and antioxidant status. Practical steps include optimizing sleep and recovery, reducing exposures, ensuring adequate dietary antioxidants and precursors for glutathione (e.g., cysteine-containing foods or supplements when indicated), and working with a clinician to address underlying inflammatory or infectious drivers.

Q: Could subtle nutrient cofactor shortfalls be undermining mitochondrial energy even with a healthy diet?

A: Yes-mitochondrial enzymes depend on micronutrients (e.g., CoQ10, riboflavin/B2, niacin/B3, B12, iron, magnesium, and carnitine). Subclinical shortages from malabsorption, medication interference, genetic polymorphisms, or increased needs can limit ATP synthesis. Symptoms are often nonspecific fatigue, muscle cramps, and decreased exercise tolerance. Blood tests and functional nutrient testing guide targeted repletion. Tailored supplementation and addressing absorption issues (e.g., H. pylori, low stomach acid) often improve energy when standard dietary intake is not enough.

Q: How can low-grade inflammation reduce mitochondrial energy production even if lifestyle appears healthy?

A: Chronic, low-level inflammation-driven by obesity, dental infections, gut dysbiosis, or autoimmune activity-reprograms cellular metabolism toward immune processes and impairs mitochondrial respiration. Cytokines and immune metabolites can block complexes in the electron transport chain and promote mitochondrial fragmentation. Symptoms include persistent fatigue, sleep disturbances, and sensitivity to exertion. Evaluation may include inflammatory markers and a search for hidden sources (dental, gut, autoimmune). Treating the source of inflammation, improving gut health, and using anti-inflammatory dietary patterns and therapies under medical guidance can restore mitochondrial function.

Q: Can circadian rhythm disruption affect mitochondria so I feel drained even with adequate sleep hours?

A: Yes. Timing misalignment (shift work, late-night light exposure, inconsistent sleep-wake schedules) disrupts mitochondrial dynamics and expression of genes involved in energy metabolism, lowering daytime ATP availability despite total sleep time. Symptoms often include daytime sleepiness, poor concentration, and mismatched energy peaks. Strategies include anchoring sleep-wake times, morning light exposure, minimizing late-night screen light, aligning meal timing with daylight, and using gradual schedule adjustments; these restore circadian signals that optimize mitochondrial efficiency.

Q: Could medications, environmental toxins, or metabolic byproducts be silently impairing my mitochondria?

A: Many common drugs (statins, certain antibiotics, some antivirals), pesticides, heavy metals, and metabolic toxins inhibit mitochondrial enzymes or promote oxidative damage, producing fatigue and muscle weakness. History of exposures, polypharmacy, and occupational risks are important to review. Testing may include toxicant panels and assessment of drug side effects. Management involves stopping or switching offenders when possible, using detoxification strategies and supportive nutrients under clinician supervision, and monitoring mitochondrial recovery through symptom tracking and functional tests.