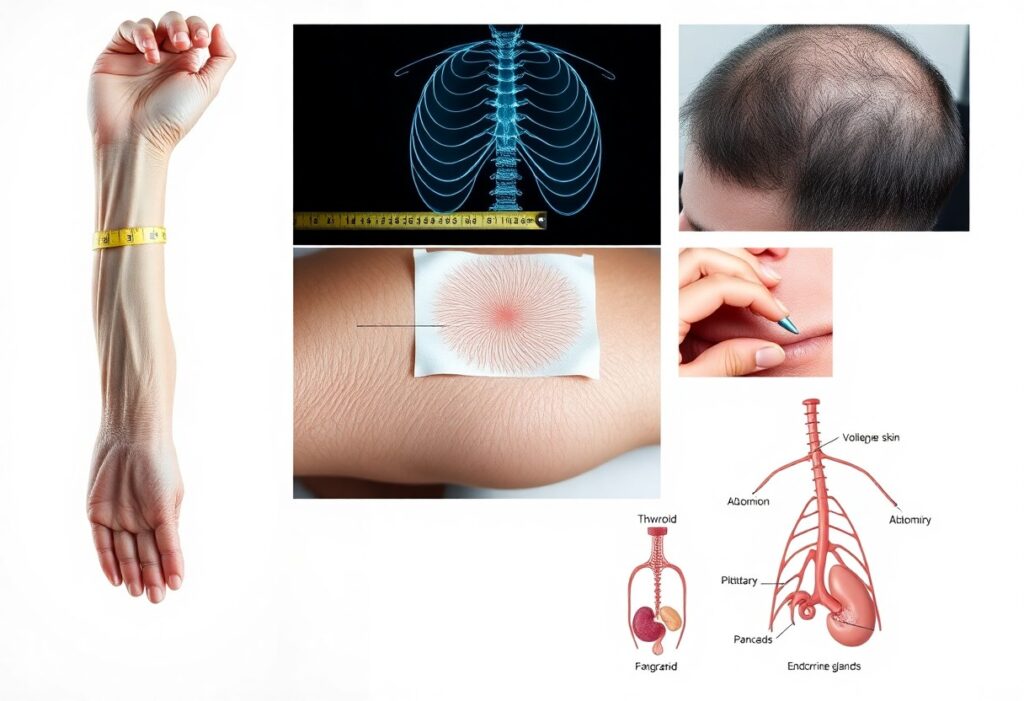

You experience predictable hormonal shifts as you age that lower energy, slow tissue repair, weaken immunity, alter metabolism, reduce muscle synthesis, disrupt sleep, and impair stress response; understanding these seven specific changes helps you identify causes of fatigue, guide targeted testing, and prioritize interventions to restore vitality and resilience so you can optimize function and recovery throughout midlife and beyond.

Key Takeaways:

- Sex hormone decline (estrogen, progesterone, testosterone) – reduced muscle mass, libido, bone density, and metabolic rate.

- Lower growth hormone/IGF‑1 activity – slower tissue repair, decreased muscle synthesis, impaired recovery.

- Thyroid shifts toward lower function – diminished energy, slowed metabolism, and cognitive sluggishness.

- HPA axis dysregulation and elevated cortisol – chronic catabolism, sleep disruption, and weakened immune responses.

- Rising insulin resistance – energy swings, increased fat storage, systemic inflammation, and metabolic disease risk.

- Falling melatonin and circadian disruption – poorer sleep quality, reduced nightly repair, and impaired cellular maintenance.

- Reduced DHEA/anabolic reserve plus low‑grade inflammation – less resilience, impaired mitochondrial function, and slower healing.

The Role of Hormones in Energy Regulation

Your day-to-day energy depends on a coordinated hormonal network-insulin, thyroid hormones, cortisol, and growth hormone-shaping how you burn, store, and repair. As you age, basal metabolic rate falls roughly 1-2% per decade after your 30s, and shifts in these hormones drive greater fatigue, slower recovery, and reduced exercise tolerance. Specific imbalances often show as post-meal sluggishness, poor sleep, or difficulty losing fat despite similar activity.

Insulin and Blood Sugar Levels

Insulin controls glucose uptake and suppresses fat breakdown, so declining insulin sensitivity with age makes you store more calories as fat and feel energy crashes after meals. Metabolic syndrome now affects about one-third of U.S. adults, and even modest insulin resistance raises fasting glucose, increases hepatic fat, and fuels low-grade inflammation-explaining why afternoon energy slumps and higher postprandial glucose spikes become more common as you get older.

Thyroid Hormones and Metabolic Rate

Thyroid hormones (T4 and active T3) set your cellular metabolic tempo, and age-related changes-TSH tending to rise and peripheral T3 often declining-slow resting energy expenditure and thermogenesis. Overt hypothyroidism occurs in ~1-2% of adults, while subclinical dysfunction can be present in up to ~10% of older individuals, manifesting as fatigue, weight gain, and reduced exercise capacity even when labs look borderline.

Beyond TSH, conversion of T4 to T3 can falter due to inflammation, nutrient deficits (selenium, zinc), or common medications, increasing reverse T3 that blocks T3 action at receptors. In practical terms, low T3 and high rT3 correlate with impaired mitochondrial function and exercise intolerance; evaluating free T3, reverse T3, and thyroid antibodies alongside symptoms gives a clearer picture than TSH alone when you’re struggling with low energy.

Hormonal Changes in Aging

Across aging, multiple endocrine axes shift simultaneously-sex hormones fall, growth/IGF-1 signals wane, thyroid set points shift, and the HPA and insulin systems remodel. You should expect these combined changes to alter body composition, sleep, healing, and metabolic flexibility. For example, testosterone drops roughly 1% per year after age 30, and early postmenopausal estrogen loss accelerates bone loss by about 2-3% annually for several years.

Decline in Sex Hormones

You experience reduced estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone with clear functional consequences: less muscle mass, lower libido, and higher fracture risk. Women typically see estradiol fall by more than 70-80% around menopause, while men lose about 1% testosterone per year after 30. Clinically, that translates into measurable declines in strength and resting metabolic rate-factors that amplify weight gain and sarcopenia if unaddressed.

Cortisol and Stress Response

HPA-axis regulation changes with age so you often show a blunted diurnal cortisol slope: smaller morning peak and higher evening levels. That pattern links to poorer sleep efficiency, increased visceral fat, and impaired glucose tolerance. In practical terms, elevated evening cortisol commonly shows up as fragmented sleep and higher fasting glucose or waist circumference despite unchanged calorie intake.

Mechanistically, reduced hippocampal feedback and prolonged adrenal activation mean cortisol exposure over decades promotes muscle catabolism, insulin resistance, and immune suppression. You can detect dysregulation with serial salivary cortisol (waking, 30-45 min, evening) and see real-world effects-caregiver stress studies demonstrate significantly slower wound healing and higher inflammatory markers-so targeting sleep, timed exercise, and stress-reduction yields measurable improvements.

Impact on Repair Mechanisms

As you age, your cellular repair systems slow: DNA repair enzymes and autophagy efficiency decline, senescent cell burden rises, and chronic low-grade inflammation increases. That combination lengthens wound-healing times, reduces collagen turnover, and impairs tissue remodeling after injury. For example, tissue tensile strength and regenerative capacity measurable in biopsy studies fall markedly after midlife, leaving you with slower recovery and greater cumulative damage over years.

Growth Hormone and Tissue Regeneration

Your pulsatile growth hormone (GH) secretion drops roughly 14% per decade after young adulthood, lowering IGF‑1 and reducing collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and satellite cell activation. That decline translates into slower bone remodeling and delayed wound closure; clinical studies show older adults with low GH/IGF‑1 have visibly poorer skin repair and diminished muscle regenerative responses after injury compared with younger controls.

Testosterone and Muscle Maintenance

Your total testosterone typically falls about 1% per year in men after age 30, and free testosterone drops even faster; women also experience lower androgen exposure with age. Since testosterone drives protein synthesis, fiber hypertrophy, and satellite cell activity, its decline accelerates age‑related muscle loss-sarcopenia-contributing to the 3-8% muscle mass loss per decade seen after midlife.

More detailed trials show that in hypogonadal men, testosterone replacement over 6-12 months often produces 2-5 kg gains in lean mass and measurable strength improvements versus placebo, and combining resistance training amplifies those effects. Mechanistically, testosterone acts via androgen receptors to enhance mTOR signaling, increase myonuclear number, and preserve neuromuscular junction integrity, so lower levels blunt both hypertrophy and functional recovery after disuse or injury.

Resilience and Adaptability

As you age, hormone shifts blunt your capacity to bounce back: the adrenal axis shows a flattened diurnal cortisol slope with higher evening cortisol, while DHEA-S falls roughly 80% between ages 20 and 80, reducing anti-inflammatory buffering. This combination slows recovery from infections, prolongs muscle catabolism after stress, and correlates with higher frailty and mortality in cohort studies.

Adrenal Hormones and Stress Resilience

Your cortisol rhythm narrows with age – peak-trough amplitude declines and recovery after acute stress is prolonged – which elevates IL-6 and CRP responses after challenges. Simultaneously, DHEA declines remove antiglucocorticoid effects, so you experience slower recuperation from sleep loss, surgery, or intense exercise and greater risk of muscle wasting and insulin resistance following repeated stressors.

Estrogen and Cellular Repair

When estrogen falls at menopause (estradiol commonly drops ~60-80%), you lose support for mitochondrial function, collagen synthesis, and DNA repair signaling, producing slower wound healing, thinner dermal collagen, and impaired bone remodeling. Many women notice measurable declines in tissue resilience within months, reflecting reduced ERα/ERβ-mediated repair pathways in skin, bone, and vasculature.

Estrogen binds ERα and ERβ to upregulate antioxidant enzymes, preserve mitochondrial membrane potential, and increase telomerase activity in endothelial cells in vitro, protecting against oxidative DNA damage. Skin studies report dermal collagen declines of about 1-2% per year after menopause, and randomized trials show estrogen therapy can improve skin thickness and wound-closure metrics, demonstrating direct tissue-level repair effects.

Lifestyle Factors Affecting Hormonal Balance

Daily routines-sleep, stress, activity, diet, alcohol and environmental exposures-shift hormone output as you age. When you sleep under 6 hours, leptin falls and ghrelin rises, increasing appetite; chronic stress elevates cortisol and suppresses testosterone and thyroid signaling. Irregular meal timing and night shifts disturb insulin and melatonin rhythms, while even occasional heavy drinking transiently lowers testosterone. Small, consistent choices matter. Perceiving these patterns lets you target the right interventions.

- Prioritize 7-9 hours of regular sleep every night.

- Use stress tools (breathing, CBT, 10-20 min/day of meditation) to lower cortisol.

- Limit alcohol to occasional intake rather than daily heavy use.

- Reduce exposure to endocrine disruptors (plastics, pesticides) and quit smoking.

- Time protein (25-30 g per meal) and moderate carbs around activity to stabilize insulin.

- Keep consistent activity: resistance 2-3×/week and daily NEAT (7,000-10,000 steps).

Nutrition and Diet

You should aim for 25-30 g of high-quality protein each meal (≈1.0-1.2 g/kg/day for older adults) to preserve muscle and anabolic signaling. Favor omega-3 fats (1-3 g/day), 25-35 g fiber daily, and minimize refined carbs to blunt insulin spikes. Time carbs around workouts to support glycogen and recovery, and use a consistent eating window (10-12 hours) if sleep or weight is disrupted to improve insulin rhythms.

Exercise and Physical Activity

You benefit most from a mix: resistance training 2-3 times weekly (compound lifts, 3-5 sets of 6-12 reps) to boost testosterone and GH, plus 1-2 HIIT sessions (10-20 minutes) to improve insulin sensitivity. Maintain daily NEAT-aim for 7,000-10,000 steps-and include balance/flexibility work to preserve function and reduce injury risk. Monitor recovery to avoid sustained cortisol elevation.

Design a simple weekly program: two full-body resistance sessions (squats, deadlifts/hip hinges, presses, rows) with progressive overload-add 2.5-5% load or 1-2 reps when sets are completed comfortably-for 8-12 weeks; include one higher-intensity session (6-8 reps) or an extra session for lagging muscle groups. Add two short cardio sessions (10-20 minute HIIT or 30-40 minute moderate cardio) and daily mobility work. Track objective markers-strength increases, resting heart rate, sleep quality, and body composition-because rising fatigue, disrupted sleep, or loss of appetite signal overtraining and warrant reduced volume or added recovery (48-72 hours for large muscle groups).

Strategies for Optimizing Hormonal Health

You should prioritize measurable, evidence-based changes: aim for 7-9 hours sleep, 150 minutes/week moderate activity plus 2 resistance sessions, and 1.0-1.2 g protein/kg to preserve muscle and metabolic rate; monitor fasting glucose, insulin, lipid panel, TSH and key sex hormones every 3-6 months; and reduce alcohol to CDC limits (≤1 drink/day women, ≤2 men) while cutting BPA and high-phthalate plastics to lower endocrine disruption.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

If you consider HRT, discuss risks and benefits with a clinician: transdermal estradiol typically has lower VTE risk than oral forms, micronized progesterone is preferred for endometrial protection, and testosterone can increase lean mass by ~2-5% over 6-12 months in deficient men. You should get baseline labs (lipids, hematocrit, PSA in men) and schedule follow-ups at 3 and 6 months to titrate dose and monitor adverse effects.

Natural Supplements and Lifestyle Changes

You can use targeted supplements and routines to support hormones: vitamin D 800-2,000 IU/day if deficient, omega‑3s 1 g/day for inflammation, magnesium 300-400 mg at night for sleep and insulin sensitivity, and limit added sugars; combine with 10-20 min HIIT twice weekly and strength training 2-3× weekly to boost growth hormone and testosterone signaling and improve glucose disposal.

Implement a practical plan: take vitamin D and omega‑3 with breakfast, magnesium before bed, consume 25-35 g protein at each meal, and follow a 12-14 hour overnight fast twice weekly; track outcomes with body composition or grip strength, fasting insulin and 25(OH)D every 3 months, and review interactions with medications (e.g., anticoagulants with omega‑3) with your provider before starting supplements.

To wrap up

With this in mind, as hormones shift you will notice declines in energy, repair, and resilience driven by changing sleep, metabolism, inflammation, muscle mass, stress response, immune function, and sex hormone levels. You can slow these effects by prioritizing sleep, targeted resistance training, protein-rich nutrition, stress management, metabolic health, and appropriate medical evaluation for hormone optimization. Early, consistent action preserves function and quality of life as you age.

FAQ

Q: How does the decline in sex hormones (estrogen and testosterone) reduce energy, repair, and resilience?

A: Lower estrogen and testosterone with age reduce muscle mass, bone density, and mitochondrial function, which lowers basal energy and slows tissue repair. Cognitive processing speed, libido, mood stability, and recovery from injury or illness can also decline. Mitigation includes resistance training, adequate protein, vitamin D and calcium for bone health, sleep optimization, and medical evaluation for hormone replacement when benefits outweigh risks under specialist guidance.

Q: What impact does reduced growth hormone (GH) and IGF‑1 signaling have on aging biology?

A: Age‑related declines in GH and IGF‑1 lower protein synthesis, slow muscle and connective tissue repair, reduce bone remodeling, and impair cellular turnover. This leads to reduced strength, poorer wound healing, and decreased capacity to respond to physiologic stress. Interventions include progressive resistance exercise, sufficient dietary protein and leucine, maintaining healthy sleep patterns, and discussing medical options with an endocrinologist if clinically indicated.

Q: Why does a drop in adrenal androgens like DHEA matter for energy and resilience?

A: Declining DHEA reduces the pool of steroid precursors available for conversion to active sex hormones and influences mood, immune function, and stress responses. Lower levels correlate with fatigue, reduced stress tolerance, and slower recovery from illness. Lifestyle measures-stress reduction, sleep, exercise, and balanced nutrition-support adrenal health; supplementation or replacement should only be considered with endocrine assessment due to mixed evidence and potential risks.

Q: How do age‑related changes in thyroid function affect metabolism and repair?

A: Even subtle declines or dysregulation of thyroid hormones slow metabolic rate, reduce cellular energy production, impair thermogenesis, and blunt protein turnover, contributing to fatigue, weight gain, and slower tissue repair. Screening for hypothyroidism is important in symptomatic people. Treatment with thyroid hormones is effective when deficiency is confirmed; optimizing nutrition (iodine, selenium), managing inflammation, and monitoring medications that affect thyroid function also help.

Q: In what ways does insulin resistance and altered metabolic signaling reduce energy and recovery?

A: Insulin resistance impairs glucose uptake and mitochondrial efficiency, promotes chronic low‑grade inflammation, and disrupts anabolic signaling needed for muscle maintenance and repair. Consequences include low energy, reduced exercise tolerance, poor wound healing, and higher disease risk. Key strategies are weight management, resistance and aerobic exercise, lowering refined carbohydrate intake, improving sleep, and medical management of metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes when present.

Q: How does HPA axis change and cortisol dysregulation undermine resilience and repair?

A: With age, circadian cortisol patterns can flatten and stress responses can become exaggerated or prolonged, which suppresses immune function, increases catabolism of muscle and bone, and impairs sleep and cognition. Chronic cortisol excess promotes inflammation and slows tissue recovery. Interventions include stress‑management techniques (mindfulness, cognitive strategies), regular physical activity, robust sleep routines aligned to natural light, and evaluation for HPA disorders if symptoms are severe.

Q: What role do declining melatonin, altered sleep, and immune aging (inflammaging) play in lowered repair and resilience?

A: Reduced melatonin and fragmented sleep impair nightly restorative processes: DNA repair, immune surveillance, and protein synthesis. Concurrent immune aging and persistent low‑grade inflammation damage tissues and diminish the ability to recover from injury or infection. Improving sleep timing and quality, optimizing light exposure (bright days, dark nights), treating sleep disorders, anti‑inflammatory dietary patterns, physical activity, and vaccination where appropriate all strengthen repair capacity and resilience.