Recovery at the cellular level determines how well your tissues repair, and when it falters you may see nine subtle signs that your cells are stressed and failing to recover properly. This post outlines those signals, why they matter, and practical steps you can take to support your cellular resilience and restore optimal function.

Cellular Stress: mechanisms and why recovery fails

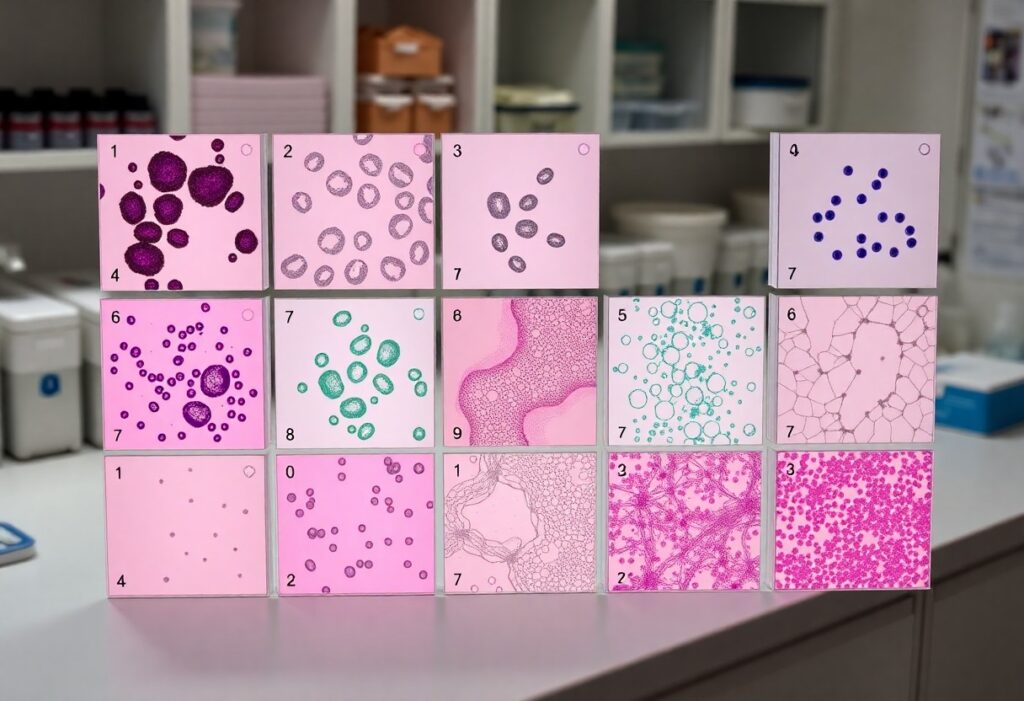

Molecularly, when your cells face stress, oxidative damage, ER stress, misfolded proteins and DNA breaks activate the unfolded protein response, ATM/ATR signaling, mitophagy and autophagy. Mitochondria supply ~90% of ATP and become a major ROS source; persistent ROS exhausts glutathione and peroxidizes lipids, disrupting membranes. Recovery fails when repair pathways are overwhelmed-chronic inflammation, senescence and telomere shortening (~50-100 base pairs per division) lock cells into dysfunctional states and impair tissue-level regeneration.

Acute vs. chronic stress responses

With acute insults your cells mount fast, coordinated responses: heat-shock proteins, transient autophagy and HPA-axis-driven cortisol surges (often 2-3× baseline) that restore proteostasis and energy balance. Chronic insults, by contrast, keep NF-κB and inflammasomes activated, elevate IL‑6 and TNFα persistently, and push cells toward senescence. You see this difference clinically in ischemia-reperfusion where recovery can follow rapid repair, versus chronic hyperglycemia in diabetes where AGEs and low-grade inflammation impede regeneration.

Cellular resilience, tipping points and maladaptation

Your cellular resilience depends on repair capacity-mitochondrial reserve, proteasome and autophagy flux, and DNA repair efficiency-and has measurable thresholds. When stress pushes systems past a tipping point, a small additional insult can flip cells into senescence, apoptosis, or maladaptive remodeling. For example, senescent-cell burden often rises from under 1% in young tissues to 10-20% with age, amplifying local inflammation and impairing regeneration, so incremental declines in clearance or autophagy produce outsized tissue dysfunction.

You can shift tipping points by enhancing clearance and repair: intermittent fasting (16-24 hours) upregulates autophagy, exercise increases mitochondrial biogenesis (PGC‑1α induction), and pharmacologic agents-rapamycin or NAD+ precursors-improve repair pathways. In mouse models, rapamycin extends median lifespan and senolytic cocktails (dasatinib + quercetin) reduce senescent-cell burden and restore tissue function. Those interventions show the tipping point is modifiable, but timing, dose and tissue specificity determine whether you restore resilience or create new maladaptation.

Metabolic red flags: energy and nutrient sensing

Your cells reveal metabolic stress through failing energy production and misread nutrient cues: reduced oxidative phosphorylation, an inability to switch between fat and carbohydrate burning (metabolic inflexibility), and chronic hyperinsulinemia or hypoglycemia. You may notice exercise intolerance, post-meal brain fog, or poor recovery after fasting; at the cellular level these map to altered RER, impaired mitochondrial respiration, and sustained activation of growth pathways that block repair and autophagy.

ATP depletion, metabolic inflexibility and glucose dysregulation

When mitochondrial ATP drops, ion pumps falter, cytosolic Ca2+ rises and you get impaired contraction, neurotransmission and repair. You’ll often see metabolic inflexibility as an RER stuck near 0.9-1.0 during fasting, indicating persistent carbohydrate reliance. In insulin-resistant muscle studies, mitochondrial oxidative capacity can be 20-40% lower, correlating with reduced ATP turnover and poorer recovery after exertion or caloric stress.

Disrupted nutrient-sensing pathways (AMPK, mTOR, insulin signaling)

AMPK senses a high AMP/ATP ratio and shifts your cell to catabolism; mTORC1 responds to amino acids and insulin to drive anabolism and suppress autophagy. If AMPK is chronically low and mTOR persistently active, you get anabolic resistance, diminished autophagy and impaired glucose uptake from defective insulin-PI3K-Akt signaling. Clinically, this shows as reduced exercise benefits, poor muscle protein turnover and blunted improvements with caloric restriction or metformin.

At the signaling level, AMPK directly phosphorylates ULK1 and TSC2 to promote autophagy and inhibit mTORC1, while mTORC1 phosphorylates S6K1 and 4E-BP1 to increase translation and cell growth. Chronic mTOR activation triggers S6K1-mediated feedback phosphorylation of IRS proteins, worsening insulin resistance and GLUT4 translocation failure. You can modulate these pathways: exercise and metformin activate AMPK; rapamycin inhibits mTOR and extends lifespan in multiple mouse models, illustrating the trade-offs between growth signaling and cellular maintenance.

Oxidative and mitochondrial distress

Mitochondria supply ~90% of your cellular ATP, so oxidative damage there hits energy first: mtDNA sustains roughly a tenfold higher mutation rate than nuclear DNA, cardiolipin peroxidation releases cytochrome c to trigger apoptosis, and chronic ROS exposure progressively fragments the network. You’ll see declines in spare respiratory capacity and rising protein carbonylation as early signals that cells can’t meet energetic demand or recover after insults.

Excess ROS, lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction

Excess ROS drives lipid peroxidation products like 4‑HNE and MDA that modify enzymes and membranes, impairing electron transport and lowering ATP output; in ischemia-reperfusion models ATP can fall 20-40%. You can track this via increased 4‑HNE staining, elevated MDA assays, loss of membrane potential (JC‑1/TMRM) and reduced oxygen consumption rate (OCR) on a Seahorse analyzer.

Impaired mitophagy and loss of bioenergetic capacity

When PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy falters, damaged mitochondria accumulate, ROS rises and ATP production drops; this is a hallmark in Parkinson’s models and aging tissues. You’ll notice higher heteroplasmy, swollen cristae on EM, and reduced spare respiratory capacity, signaling that turnover isn’t keeping pace with damage and your cells are sliding toward functional decline.

Digging deeper, you can quantify mitophagy defects with mt‑Keima reporters, LC3 co‑localization, and assays of membrane potential (TMRM) plus mitophagy markers (PINK1, Parkin, BNIP3). Functional thresholds matter: when pathogenic mtDNA heteroplasmy exceeds ~60% in many tissues, OXPHOS fails. Interventions that boost mitophagy-exercise, NAD+ precursors, spermidine or urolithin A-have shown reproducible improvements in mitochondrial biomarkers in preclinical and early human studies.

Inflammatory and immune indicators

You’ll see systemic signs when cellular stress drives immune activation: persistently elevated hs-CRP, frequent low-grade fevers, new autoantibodies, or poor wound healing. Clinical labs often show hs-CRP in the 1-3 mg/L range for low-grade inflammation and >3 mg/L for higher risk; chronically raised IL-6 and TNF-α accompany fatigue, insulin resistance, and accelerated tissue remodeling.

Chronic low-grade inflammation and cytokine shifts

When you have chronic low-grade inflammation, adipose and senescent cells keep secreting IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α, tipping your cytokine balance toward a pro-inflammatory state. For example, people with obesity often show hs-CRP >2 mg/L and elevated IL-6, which promotes insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, increasing cardiovascular risk even without overt infection.

Immune senescence and impaired clearance of damaged cells

As you age or accumulate stress, thymic output and naive T-cell pools fall while CD28- senescent T cells expand, sometimes comprising a large fraction of CD8+ cells; vaccine responses can drop from ~60% effectiveness in younger adults to ~30-40% in those over 65. That impaired cytotoxic clearance lets damaged and senescent cells persist, sustaining local inflammation.

More specifically, persistent senescent-cell accumulation produces a SASP rich in IL-6, IL-8 and MMPs that degrades tissue microenvironments and impairs regeneration. You can monitor markers such as elevated p16INK4a expression, shorter telomeres, or an inverted CD4/CD8 ratio to gauge immune aging; animal studies show senolytic clearance of these cells reduces systemic IL-6 and improves organ function, illustrating mechanistic links you can target clinically or experimentally.

Genomic instability and repair failure

When your cells accumulate unrepaired DNA lesions and lose telomeric protection, genomic instability becomes a driving force behind senescence, organ decline and cancer. Each cell sustains roughly 10,000-100,000 DNA lesions daily; failure to correct double‑strand breaks, mismatches or oxidative base damage rapidly raises mutation burden and dysregulated gene expression, accelerating tissue dysfunction even before clinical disease appears.

Accumulation of DNA damage and telomere attrition

Your telomeres shorten by about 50-200 base pairs each division, leaving newborns with ~10-15 kb and many older adults with 4-6 kb. As telomeres approach a critical length they trigger persistent DNA damage responses that force senescence or apoptosis. In disorders like dyskeratosis congenita or pulmonary fibrosis, accelerated attrition causes organ failure decades earlier than expected.

Faulty DNA repair pathways and mutation burden

Defects in homologous recombination, mismatch repair or base‑excision pathways let mutations accumulate unchecked, raising your mutation burden and cancer risk. For example, BRCA1/2 loss impairs double‑strand break repair; mismatch repair deficiency produces microsatellite instability seen in ~15% of colorectal cancers. High tumor mutation burden (often measured as mutations per megabase) correlates with neoantigen load and therapy responses.

When homologous recombination fails you rely more on error‑prone nonhomologous end joining, increasing structural variants; BRCA1 carriers face roughly 45-65% lifetime breast cancer risk and 39-44% ovarian risk. Tumors with mismatch repair deficiency or POLE mutations become ultramutated and frequently respond to immune checkpoint blockade-pembrolizumab is approved for MSI‑high cancers. Also note clonal hematopoiesis affects about 10% of people over 65, raising cardiovascular and leukemia risks by permitting expansion of mutant clones.

Senescence, tissue remodeling and clinical clues

SASP, impaired stem cell function and regenerative failure

Senescent cells secrete a SASP rich in IL‑6, IL‑8, TNFα, MMPs and ROS that propagates local inflammation and suppresses regeneration. You see this in aged muscle and bone marrow: senescent-cell burden can reach roughly 10-15% in elderly tissues, and mouse studies show clearing p16Ink4a+ cells restores satellite cell proliferation and tissue repair. Persistent SASP signaling blunts hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cell function, reducing your capacity to recover after injury.

Fibrosis, altered extracellular matrix and systemic biomarkers

Fibrosis arises when activated myofibroblasts deposit collagen I/III and fibronectin under sustained TGF‑β1 signalling, stiffening the ECM and impairing organ mechanics. You can pick this up systemically with elevated P3NP, hyaluronic acid or TGF‑β1 levels, and locally via elastography-liver stiffness above ~12 kPa commonly indicates advanced fibrosis. Progressive ECM accumulation raises inflammatory markers and predicts worse outcomes across lung, liver and heart disease.

At the molecular level, TGF‑β drives fibroblast→myofibroblast conversion with α‑SMA upregulation while an MMP/TIMP imbalance blocks ECM turnover, causing capillary rarefaction and tissue hypoxia. You can monitor progression clinically: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis carries a median survival of ~3-5 years, and rising P3NP correlates with adverse cardiac and hepatic outcomes; serial elastography plus P3NP trends help gauge response to antifibrotic therapy.

To wrap up

To wrap up, your cells send subtle warnings-persistent fatigue, poor sleep, recurring infections, slow healing, brain fog, unexplained weight shifts, chronic inflammation, metabolic changes, and increased oxidative markers-that indicate stress and impaired recovery. Act on these signals by optimizing nutrition, sleep, stress management, and medical evaluation to help you restore cellular resilience and prevent long-term decline.