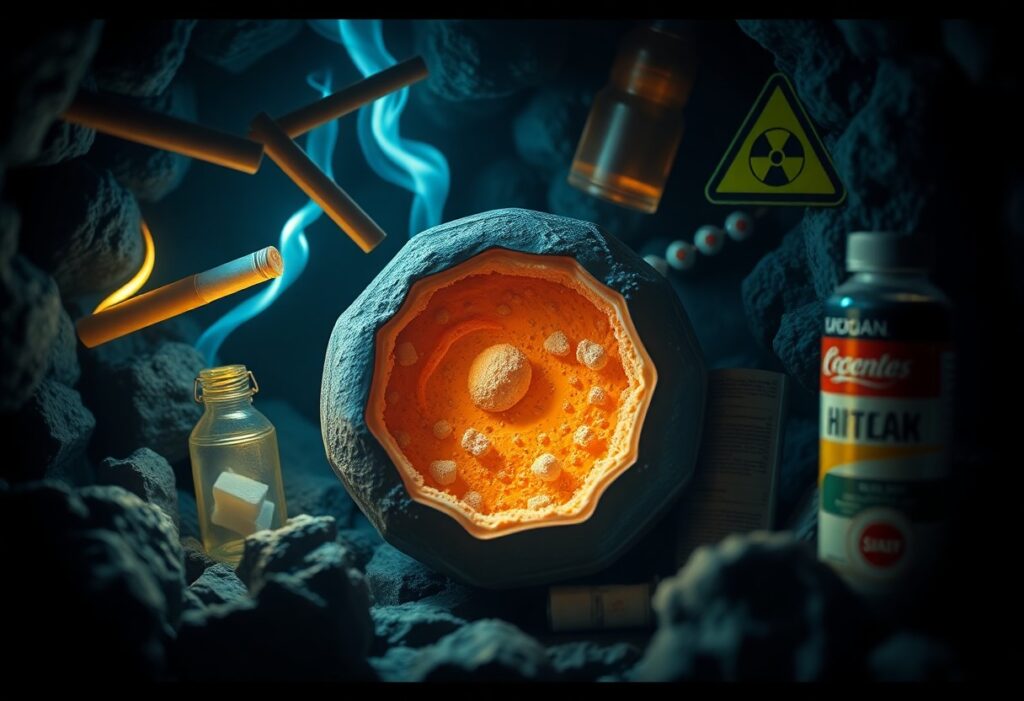

Most everyday exposures and habits quietly erode mitochondrial function, reducing your cellular energy and resilience over time. In this article you’ll learn nine shocking stressors – environmental toxins, chronic inflammation, poor sleep, metabolic imbalance, certain medications, excessive exercise, nutrient deficiencies, psychological stress, and aging-related decline – what they do to your mitochondria and practical, evidence-based steps you can take to protect and restore your cellular energy.

Just as your cells rely on mitochondria to produce the ATP that powers every action, chronic exposures and lifestyle factors quietly impair this energy engine and sap your resilience. In this post you’ll learn nine shocking stressors-from environmental toxins and poor sleep to persistent inflammation and nutrient shortfalls-that undermine mitochondrial efficiency, how they disrupt your cellular energy, and practical steps you can take to protect it.

Mitochondrial structure, function and vulnerability

Your mitochondria are double-membraned organelles with an inner membrane folded into cristae, a matrix that houses the TCA cycle, and their own 16.6 kb genome encoding 37 genes. Because the inner membrane concentrates electron flow and protons, it becomes a hotspot for reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation and calcium overload. Structural disruption of cristae or outer membrane permeabilization quickly impairs ATP output and releases signals that drive inflammation and cell death.

ATP production and the electron transport chain

You generate most ATP via the electron transport chain: Complexes I-IV shuttle electrons from NADH/FADH2 to oxygen, pumping protons into the intermembrane space; Complex V (ATP synthase) returns protons to make ~30 ATP per glucose under aerobic conditions. High-energy tissues like heart rely on oxidative phosphorylation for >80-90% of ATP. Complexes I and III are major ROS sources, and inhibitors such as cyanide (Complex IV) or rotenone (Complex I) quickly shut down cellular energy.

Dynamics: fusion, fission and mitophagy

You maintain mitochondrial quality through fusion (MFN1/2, OPA1), fission (DRP1) and mitophagy (PINK1/Parkin). Fusion mixes contents to dilute damage and preserve membrane potential; fission isolates dysfunctional fragments; mitophagy clears those fragments. Imbalances produce fragmented networks, lower ATP and higher ROS, and are observed in neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson and optic atrophy linked to PINK1/Parkin and OPA1 defects.

Fusion allows mixing of mtDNA and protein components to buffer mutations, while fission segregates depolarized units for autophagic removal. DRP1 recruitment is regulated by phosphorylation and adaptor proteins (Fis1, Mff); Parkin ubiquitinates outer membrane proteins after PINK1 stabilization on damaged mitochondria, tagging them for autophagosomes. In cell models, excessive DRP1 activity increases ROS and reduces spare respiratory capacity; conversely, enhancing fusion or PGC‑1α-mediated biogenesis restores function.

Genetic, age-related and drug-related susceptibilities

Your mitochondrial genome is more mutation-prone than nuclear DNA-about tenfold higher-encoding 13 ETC proteins, 22 tRNAs and 2 rRNAs. Heteroplasmy means mutant load must often reach ~60-90% before symptoms appear. With age, deletions and copy-number loss accumulate in muscle and brain. Drugs such as NRTIs (zidovudine, stavudine) inhibit POLG causing mtDNA depletion; aminoglycosides precipitate hearing loss in m.1555A>G carriers; linezolid can induce lactic acidosis by blocking mitochondrial translation.

Inherited syndromes illustrate this vulnerability: LHON arises from specific complex I mtDNA mutations causing sudden optic neuropathy in young adults, while MELAS (mitochondrial encephalomyopathy) involves tRNA mutations and stroke-like episodes. Longitudinal studies show aged skeletal muscle accumulates ~30-50% more mtDNA deletions versus young adults, correlating with sarcopenia. Clinically, screening for mtDNA variants can inform antibiotic or antiviral choices to avoid iatrogenic mitochondrial failure.

Mitochondria at a glance

Inside most of your cells you’ll find hundreds to thousands of mitochondria – 0.5-10 µm organelles housing their own genome (37 genes in human mtDNA) and producing over 90% of cellular ATP via oxidative phosphorylation; they also generate ROS, buffer calcium, and trigger programmed cell death when damaged, so their number and health directly shape tissue function from muscle performance to brain resilience.

Core functions: ATP production, signaling and apoptosis

When you need energy mitochondria run oxidative phosphorylation through complexes I-V to make roughly 30-32 ATP per glucose, far outpacing the 2 ATP from glycolysis; they also modulate cytosolic calcium, generate ROS that act as signaling messengers, and release cytochrome c to activate caspases during apoptosis, so defects in any complex or excessive ROS can quickly impair cellular energetics and survival.

Dynamics and quality control: fusion, fission, biogenesis and mitophagy

You rely on constant mitochondrial remodeling: fusion (MFN1/2, OPA1) mixes contents to dilute damage, fission (DRP1) segregates defective units for removal, biogenesis driven by PGC‑1α/NRF1/TFAM scales organelle mass, and mitophagy (PINK1/Parkin pathway) clears irreparably damaged mitochondria-disruption in these pathways is linked to disorders like Parkinson’s and heart failure.

In practice you see fusion and fission occur on timescales from minutes to hours, and mtDNA copy numbers vary widely by cell type (roughly 100-10,000 copies per cell), influencing how mutations propagate; when mitochondria lose membrane potential PINK1 accumulates on the outer membrane, recruits Parkin to ubiquitinate proteins and tag the organelle for autophagic removal, while PGC‑1α induction-via exercise or cold exposure-upregulates TFAM to expand mitochondrial mass, illustrating how physiology and pathology (Parkin/PINK1 mutations in familial Parkinson’s) converge on these quality‑control mechanisms.

Environmental toxicants that erode energy production

Everyday exposures-from traffic fumes to contaminated groundwater-chip away at your mitochondria over years. Ambient pollutants and industrial chemicals generate persistent oxidative stress, damage mitochondrial DNA and membranes, and lower ATP output. The WHO links outdoor air pollution to millions of premature deaths worldwide, and occupational studies show that chronic low-dose exposures accelerate mitochondrial dysfunction in blood and tissue samples, so your cumulative burden matters more than single high-dose events.

Air pollution and particulate matter

Fine particles (PM2.5, <2.5 µm) penetrate deep into lungs, enter circulation, and reach tissues where they trigger ROS and inflammation. You can lose mitochondrial membrane potential and see reduced ATP production after repeated urban exposure; studies report associations between PM2.5 exposure and lower mitochondrial DNA copy number in blood. Chronic exposure also amplifies systemic oxidative damage that progressively impairs electron transport chain efficiency.

Pesticides, solvents and heavy metals

Common pesticides (rotenone, paraquat, organophosphates), organic solvents (benzene, trichloroethylene) and heavy metals (lead, mercury, cadmium) directly target mitochondrial enzymes and membranes. You may accumulate these agents via food, water, or work; they inhibit complex I-IV, generate excess superoxide, and uncouple oxidative phosphorylation, producing lasting declines in cellular energy output even at subacute doses.

Rotenone and paraquat are classic complex I inhibitors used to model Parkinsonian neurodegeneration in animals, illustrating how mitochondrial inhibition links to cell loss. Mercury binds thiol groups on mitochondrial proteins, cadmium disrupts calcium handling and opens the permeability transition pore, and many organophosphates promote persistent ROS that fragment mtDNA. You face compounded risk when multiple toxicants co-occur, since synergistic effects accelerate loss of respiratory capacity and impair mitophagy, allowing dysfunctional mitochondria to accumulate.

The 9 stressors that damage mitochondrial energy production

You face nine dominant stressors that erode mitochondrial ATP output over years: oxidative stress, environmental toxins, chronic inflammation, metabolic overload, nutrient shortfalls, psychological stress, sleep disruption, inactivity or overtraining, and aging-related decline; together they impair electron transport, lower mitochondrial DNA copy number, increase ROS, and reduce biogenesis-factors shown in dozens of human and animal studies to cut respiratory capacity and raise fatigue and disease risk.

Oxidative stress and excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS)

You generate ROS during normal respiration-superoxide and hydrogen peroxide from the electron transport chain-and when levels rise beyond antioxidant capacity they oxidize mtDNA, cardiolipin, and Complex I-IV proteins; persistent ROS exposure can drop ATP production, trigger mitophagy, and raise mutation rates in mtDNA that perpetuate dysfunction.

Environmental toxins and heavy metals (pesticides, mercury, air pollution)

You encounter pesticides like rotenone and paraquat that inhibit Complex I, mercury that binds thiols and blocks multiple complexes, and PM2.5 from air pollution that correlates with lower mitochondrial DNA copy number; these exposures directly impair oxidative phosphorylation and amplify ROS generation in cells you depend on.

You should note specific mechanisms: rotenone models produce Parkinsonian neurodegeneration by blocking Complex I; mercury forms adducts with glutathione and mitochondrial enzymes, decreasing ATP synthesis; epidemiological studies link chronic PM2.5 exposure to reduced mitochondrial respiration and systemic inflammation, especially in urban populations and agricultural workers.

Chronic inflammation and immune activation

You experience cytokine-driven mitochondrial suppression when TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 remain elevated-immune mediators that reduce oxidative phosphorylation, fragment mitochondrial networks, and push cells toward glycolysis, lowering your cellular energy efficiency and resilience during prolonged inflammation.

You should understand molecular links: activated macrophages release nitric oxide that inhibits Complex IV, NLRP3 inflammasome activation promotes mitochondrial ROS release, and chronic cytokine exposure downregulates PGC-1α, cutting biogenesis-mechanisms observed in rheumatoid arthritis, chronic infections, and metabolic syndrome cohorts.

Metabolic overload: hyperglycemia and lipotoxicity

You overload mitochondria when excess glucose and free fatty acids flood the TCA cycle, elevating electron donors and driving ROS; persistent hyperglycemia and saturated fats like palmitate produce mitochondrial fragmentation, cardiolipin oxidation, and impaired ATP output seen in type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease.

You should note specifics: high glucose increases NADH/FADH2 ratios that over-reduce the ETC and raise superoxide; palmitate induces ceramide accumulation and mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, while chronic nutrient excess suppresses mitophagy and reduces respiratory chain efficiency in muscle and liver.

Nutrient deficiencies and micronutrient imbalance

You limit mitochondrial function when cofactors go missing: CoQ10, B2 (riboflavin), B3 (niacin/NAD+), iron, magnesium, selenium, and copper are imperative for electron carriers, antioxidant enzymes, and ATP synthase-deficits lower ATP synthesis and increase vulnerability to oxidative damage.

You should act on evidence: niacin deficiency reduces NAD+ and slows dehydrogenases, iron deficiency impairs cytochromes and Complex III/IV, and low selenium compromises glutathione peroxidase activity; clinical trials show CoQ10 or B-vitamin repletion often restores respiratory parameters in deficient patients.

Chronic psychological stress and elevated glucocorticoids

You alter mitochondrial dynamics under prolonged cortisol exposure: elevated glucocorticoids shift fuel use, suppress PGC-1α-driven biogenesis, and increase mitochondrial ROS, contributing to lower ATP production and reduced mitochondrial DNA copy number reported in chronic stress studies.

You should note pathways: sustained HPA-axis activation downregulates mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM), reduces mitochondrial replication, and impairs mitophagy balance; longitudinal studies link chronic psychosocial stress to measurable declines in leukocyte mitochondrial function and energy reserve.

Sleep disruption and circadian misalignment

You disrupt mitochondrial timing when sleep is fragmented or circadian rhythms are misaligned: core clock genes (CLOCK, BMAL1) regulate mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration, and shift work or chronic sleep loss reduces mitochondrial oxidative capacity and increases ROS in brain and muscle.

You should consider mechanisms and data: sleep restriction lowers SIRT1 and AMPK signaling that support mitochondrial turnover, alters NAD+/NADH ratios, and epidemiological studies show night-shift workers exhibit reduced mitochondrial function and higher metabolic disease incidence compared with day workers.

Physical inactivity and overtraining

You harm mitochondria at both extremes: sedentary behavior decreases mitochondrial density and enzymatic activity in skeletal muscle within weeks, while chronic overtraining elevates ROS and inflammation that damage mitochondrial membranes and impair recovery, reducing your endurance and metabolic flexibility.

You should balance exercise: endurance training upregulates PGC-1α and increases mitochondrial content and VO2max, whereas prolonged excessive high-intensity training without adequate recovery raises markers of oxidative damage and lowers mitochondrial respiratory control ratios in athletes studied after overreaching.

Lifestyle and metabolic stressors

You face a convergence of sedentary behavior, excess visceral fat and poor dietary choices that drive insulin resistance, systemic inflammation and elevated circulating free fatty acids – all of which blunt mitochondrial ATP production and biogenesis. Clinical and animal data link metabolic syndrome components with lower mitochondrial density in skeletal muscle and liver and chronically elevated mitochondrial ROS, gradually eroding cellular energy reserves over years.

Processed diets, high sugar and metabolic dysfunction

Ultra‑processed foods and high added‑sugar intake overload your liver with fructose and glucose, promoting de novo lipogenesis, glycation and mitochondrial ROS. When more than ~10-15% of your daily calories come from added sugars – a common pattern – you raise fasting triglycerides and worsen insulin sensitivity; both human and rodent studies show this pattern reduces mitochondrial respiration and impairs mitophagy, accelerating dysfunction.

Chronic psychological stress and circadian disruption

Chronic stress plus circadian misalignment amplify mitochondrial damage by raising cortisol and sympathetic drive while degrading sleep quality and melatonin signaling. Short‑term sleep restriction (4-5 hours/night for a week) can cut insulin sensitivity by ~20-30%, and shift‑work meta‑analyses report roughly 20-50% higher metabolic syndrome risk-conditions that accelerate mitochondrial decline and reduce cellular energy output.

When your evening cortisol remains elevated and melatonin is suppressed, key regulators like PGC‑1α and NRF1 are downregulated, reducing mitochondrial biogenesis; at the same time persistent sympathetic activation increases ROS and impairs mitophagy so damaged mitochondria accumulate. If you restore consistent sleep timing, optimize light exposure and lower chronic stress, multiple clinical and animal studies report improved PGC‑1α activity and measurable gains in mitochondrial respiration and cellular ATP production.

Oxidative and inflammatory insults

You see oxidative and inflammatory insults converging on mitochondria through ROS/RNS generation and cytokine signaling; complexes I and III are primary ROS sources while TNF-α and IL-6 activate NF-κB, suppress PGC-1α-driven biogenesis, and promote Drp1-mediated fission, so over years mtDNA lesions like 8-oxo-dG accumulate, ATP synthesis drops, and dysfunctional mitochondria build up in tissues affected by obesity, aging, autoimmune disease and chronic infections.

Chronic inflammation and sustained reactive oxygen species

Sustained low-grade inflammation keeps ROS elevated and interferes with mitochondrial turnover: you get persistent NF-κB signaling, reduced PGC-1α expression, impaired mitophagy, and fragmented networks via increased Drp1 activity; clinically this maps to higher CRP (>3 mg/L) in metabolic syndrome and progressive declines in respiratory capacity and ATP output that worsen tissue fatigue and insulin resistance.

Persistent infections and immune-mediated mitochondrial damage

Long-term pathogens-HIV, HCV, CMV, Borrelia, and post‑viral syndromes like long COVID-drive ongoing immune activation that exposes your mitochondria to nitric oxide, peroxynitrite and burst ROS from phagocytes; the result is inhibition of complexes I/IV, mtDNA strand breaks, and symptomatic energy failure such as chronic fatigue and cognitive fog.

At the mechanistic level, cytotoxic T cells and iNOS‑expressing macrophages flood sites with RNS that nitrate respiratory proteins while some viral proteins directly target mitochondrial machinery-for example SARS‑CoV‑2 ORF9b binds TOM70 and alters MAVS signaling, HIV Vpr perturbs membrane integrity, and HCV core localizes to mitochondria raising Ca2+ and ROS; studies report mtDNA copy number reductions of ~20-40% and increased 8-oxo-dG in affected patients, linking immune-driven damage to measurable mitochondrial decline.

Medical and physical exposures

Radiotherapy doses (commonly 30-70 Gy) and cumulative diagnostic exposures (CT scans ~1-20 mSv each) accelerate mitochondrial ROS production and mtDNA deletions, while prolonged ICU hyperoxia and repeated procedures compound oxidative phosphorylation loss. You often experience these insults in combination, producing lasting ATP decline and increasing heteroplasmy, so clinical exposures can add measurable mitochondrial damage on top of lifestyle and aging-related stressors.

Certain pharmaceuticals (some antibiotics, statins, chemotherapies)

Aminoglycosides (gentamicin), linezolid and chloramphenicol bind mitochondrial ribosomes, halting protein synthesis and causing lactic acidosis or aminoglycoside-related hearing loss in carriers of the m.1555A>G mutation. Statins can lower CoQ10 by up to ~40%, impairing electron transport, and chemotherapies such as doxorubicin and cisplatin generate ROS and mtDNA lesions-doxorubicin cardiotoxicity rises sharply above cumulative doses of 400-550 mg/m².

Ionizing radiation and excessive UV exposure

Ionizing radiation fragments mtDNA and oxidizes mitochondrial lipids, while UVA penetrates to mitochondria in skin cells and drives ROS that disrupt membrane potential and ATP synthesis; therapeutic radiation and repeated medical imaging both increase this burden, and you accumulate damage with each unprotected exposure, raising long-term mitochondrial dysfunction risk.

Because mitochondria lack robust double-strand break repair, you accumulate point mutations and large-scale mtDNA deletions after radiation, producing heteroplasmy that reduces complex I/IV activity-clinical studies report persistent declines months to years after thoracic or pelvic radiotherapy, often linked to fatigue or cardiac issues. Excessive UVA from tanning beds produces comparable mitochondrial ROS, and when combined with preexisting mtDNA variants your cells can cross an energetic threshold where ATP production and tissue function fail.

Pharmaceuticals and diagnostic chemicals (antibiotics, statins, chemotherapy, anesthetics)

Drug-induced mitochondrial damage: agents and evidence

Many drugs directly impair mitochondrial function: statins can lower plasma CoQ10 by 20-40% and blunt complex I activity, antibiotics like chloramphenicol and aminoglycosides inhibit mitochondrial ribosomes (the m.1555A>G variant heightens aminoglycoside ototoxicity), and chemotherapeutics such as doxorubicin produce ROS that cause dose‑dependent cardiomyopathy above cumulative 400-550 mg/m2. Anesthetics (propofol infusion >4 mg/kg/h, prolonged volatile agents) and iodinated contrast also trigger oxidative stress in renal and neural mitochondria, so you should weigh benefits against long‑term mitochondrial risk.

Cellular and molecular mechanisms of progressive mitochondrial decline

You’ll see progressive mitochondrial decline arise from interacting molecular failures: accumulating mtDNA lesions, weakened biogenesis and mitophagy, and electron transport chain (ETC) breakdown that together lower ATP output and raise ROS. Human mtDNA is only 16,569 bp encoding 13 OXPHOS proteins, so small insults compound quickly; heteroplasmy shifts and organ-specific turnover rates mean dysfunction often appears gradually in high-energy tissues like brain, heart and skeletal muscle.

mtDNA damage and mutation accumulation

You experience mtDNA damage from replication errors, deamination and ROS-driven base modifications; repair capacity is limited compared with nuclear DNA. Somatic point mutations and deletions-such as the common 4,977 bp deletion-accumulate with age, raising heteroplasmy. Once mutant load crosses tissue-specific thresholds (often ~60-90% for respiratory defects), ATP synthesis drops and cells shift toward glycolysis, promoting dysfunction in neurons and cardiomyocytes.

Impaired biogenesis and defective mitophagy

Your ability to replace damaged mitochondria falters when regulators like PGC‑1α, NRF1/2 and TFAM are downregulated, reducing mtDNA replication and organelle synthesis. When PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is compromised-mutations in PRKN or PINK1 as in familial Parkinson’s-you accumulate dysfunctional mitochondria, increasing ROS and inflammatory mtDNA release that worsen cellular energetics.

Specifically, mitochondrial turnover occurs on timescales of days to weeks (heart mitochondria ~10-17 days, skeletal muscle longer), so a ~30-50% decline in biogenesis signaling rapidly shifts the steady-state toward older, damaged organelles. Impaired mitophagy also elevates heteroplasmy and activates cGAS‑STING and NLRP3 pathways, linking energy failure to chronic inflammation and progressive tissue loss.

Electron transport dysfunction, membrane damage and bioenergetic failure

You suffer bioenergetic collapse when ETC complexes I-IV are inhibited or mutated, cardiolipin is peroxidized and inner membrane potential (Δψm) falls. Normal Δψm ranges −140 to −180 mV; losses below ~−120 mV impair ATP synthase, lower ATP yields (from ~30 ATP/glucose toward much less) and increase superoxide, exacerbating mtDNA and lipid damage.

Complex I defects are common in aging and reduce NADH oxidation, forcing NAD+ depletion and metabolic rewiring. Oxidized cardiolipin loosens cytochrome c binding, promoting apoptosis and further reducing coupling efficiency. As Δψm collapses, ATP synthase can reverse, hydrolyzing ATP to maintain membrane potential-an energetically catastrophic outcome that accelerates cellular decline.

Age‑related mitochondrial decline

With advancing age, your cellular powerhouses lose efficiency: ATP production and respiratory capacity decline roughly 30-50% in many tissues, while reactive oxygen species and metabolic inflexibility increase. In high‑demand organs like brain and skeletal muscle, this shift contributes to sarcopenia, cognitive slowdown and slower recovery after stress, so cumulative mitochondrial dysfunction becomes a major driver of age‑associated energy deficits.

mtDNA damage, mutations and cumulative wear

Oxidative stress and replication errors produce mtDNA point mutations and deletions-including the 4,977‑bp “common deletion”-which accumulate with age and create heteroplasmy. When defective genomes exceed tissue‑specific thresholds (often >60% in muscle fibers), you observe electron transport chain failures and cytochrome c oxidase-negative fibers. Longitudinal studies detect rising somatic mtDNA mutation loads in brain and heart, linking mutation burden to functional decline and higher disease risk.

Reduced biogenesis, impaired mitophagy and loss of resilience

As you age, signaling that drives mitochondrial renewal weakens: PGC‑1α, SIRT1 and AMPK activity falls and mtDNA copy number declines, while mitophagy pathways (PINK1/Parkin) become less efficient. The result is accumulation of damaged organelles, reduced spare respiratory capacity and poorer adaptation to metabolic stress, so transient insults that were once tolerated now provoke larger energetic crises in cells and tissues.

Rodent studies report age‑related drops in PGC‑1α expression and mtDNA copy number up to ~50%, and human endurance training can raise PGC‑1α and mtDNA by ~20-40%, demonstrating partial reversibility. Interventions that boost NAD+ (NR/NMN) or activate AMPK improve mitophagy and respiratory capacity in preclinical models; early human trials show mixed but encouraging signals. If you allow renewal and clearance to fail, damaged mitochondria persist and amplify ROS, inflammation and metabolic instability over decades.

Clinical consequences and measurable biomarkers

Systemic and organ-specific presentations (neuro, muscle, metabolic)

You may present with encephalopathy, seizures, stroke-like episodes (MELAS), or subacute optic neuropathy (LHON), alongside proximal myopathy, exercise intolerance and intermittent elevated CK. Metabolic signs commonly include persistent lactic acidosis (>2 mmol/L), early-onset diabetes or insulin resistance, and cardiomyopathy-hypertrophic or dilated-often manifesting in your 20s-40s. Clinical trajectories vary: one organ system can dominate initially while multisystem decline unfolds over years.

Laboratory and imaging markers (lactate, ATP assays, mtDNA copy number, functional tests)

You’ll often find elevated blood or CSF lactate (>2 mmol/L) and an increased lactate:pyruvate ratio (>20) indicating OXPHOS impairment. ATP production assays from muscle or fibroblasts quantify functional deficit, while mtDNA copy number by qPCR identifies depletion syndromes (e.g., TK2, POLG). Functional testing-31P‑MRS, graded exercise with VO2 peak, and phosphocreatine recovery-documents impaired bioenergetics and exercise intolerance objectively.

In specialized labs you can measure oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and spare respiratory capacity in patient fibroblasts or muscle, and blue‑native PAGE detects complex I-V assembly defects. mtDNA sequencing provides heteroplasmy percentages-often >60% for severe phenotypes though tissue thresholds vary. Imaging complements labs: MELAS shows lactate peaks on 1H‑MRS and stroke‑like MRI lesions, while 31P‑MRS noninvasively tracks ATP flux and recovery kinetics.

Differential diagnosis and red flags

You must separate mitochondrial disease from endocrine disorders (thyroid, adrenal), inflammatory myopathies, toxic/drug‑induced mitochondrial dysfunction (statins, valproate), and common metabolic conditions. Red flags that mandate urgent evaluation include acute lactic acidosis (>5 mmol/L), new refractory seizures, stroke‑like episodes before age 40, progressive external ophthalmoplegia, maternal inheritance pattern, or unexplained cardiomyopathy with conduction block.

When you encounter these red flags, initiate immediate testing: serum and CSF lactate, arterial blood gas, CK, ECG and cardiac enzymes, plus brain MRI with MRS and prompt genetics referral for mtDNA and nuclear gene panels. Avoid mitochondrial toxins (notably valproate) while workup proceeds. Reserve muscle biopsy with respiratory chain assays and histology for cases where noninvasive tests and sequencing remain inconclusive.

Conclusion

Now that you’ve seen how nine shocking stressors-oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, poor sleep, high-sugar diets, environmental toxins, certain medications, sedentary behaviour, psychological stress, and nutrient deficiencies-slowly erode mitochondrial function, you must act to protect your cellular energy. Mitigate exposures, improve diet and sleep, exercise regularly, and work with clinicians to correct deficiencies and medication risks so your mitochondria sustain energy production and long-term health.

Prevention and mitigation strategies

You can blunt progressive mitochondrial decline by combining lifestyle changes, targeted supplements, and exposure reduction while regularly reviewing medications with your clinician; interventions like 150 minutes/week of aerobic exercise plus two strength sessions, a Mediterranean-style diet, and 7-9 hours sleep each night consistently show measurable improvements in mitochondrial biomarkers and functional outcomes in middle-aged and older adults.

Lifestyle optimization: diet, exercise, sleep and stress management

You should aim for 150 minutes/week of moderate aerobic activity plus two resistance sessions to stimulate PGC‑1α-driven mitochondrial biogenesis, follow a Mediterranean-pattern diet rich in oily fish, nuts, and polyphenols, get 7-9 hours of sleep to preserve mitophagy, and practice 10-20 minutes/day of mindfulness or HRV biofeedback to lower chronic cortisol that impairs electron transport chain function.

Targeted nutrients and therapeutics (CoQ10, NAD+ precursors, antioxidants)

You may benefit from evidence-backed doses: CoQ10 100-300 mg/day for statin-associated deficiency, NAD+ precursors like nicotinamide riboside or NMN in the 250-500 mg/day range, and antioxidants such as alpha‑lipoic acid 300-600 mg and vitamin C 500-1,000 mg to reduce oxidative damage-use clinical monitoring and check interactions before starting.

CoQ10 functions as an electron carrier and membrane antioxidant, while NR/NMN raise NAD+ to activate sirtuins and improve mitochondrial turnover; small randomized trials report improved muscle endurance or reduced fatigue in older adults, and mechanistic studies show restored complex I/III activity-tailor choices to clinical context, monitor liver enzymes and glucose, and coordinate dosing with your healthcare provider.

Reducing exposures and reviewing medications

You should eliminate tobacco, limit indoor PM2.5 with HEPA filtration, wash or choose organic for high‑pesticide produce, and ask your clinician to screen for heavy metals and evaluate meds with mitochondrial liability; some drugs and environmental toxicants accelerate mitochondrial damage and reversing exposures often stabilizes energy function.

For example, statins can lower plasma CoQ10 by ~30% in some studies, doxorubicin causes dose‑dependent mitochondrial cardiotoxicity, and chronic PM2.5 exposure correlates with reduced mitochondrial DNA copy number in epidemiologic cohorts; ask for blood lead and mercury tests if indicated, review alternatives or supplements with your prescriber, and implement workplace controls or PPE when occupational exposures are present.

Practical guidance for clinicians and individuals

Integrate exposure control, targeted screening and symptom quantification: document medications (statins, valproate, aminoglycosides), occupational toxins, alcohol (>14 drinks/week) and BMI; order baseline labs (CMP, TSH, fasting glucose, HbA1c, lipid panel), serum lactate and CK, ECG/audiology, and a 6‑minute walk or PROM score; schedule follow-up every 3-6 months for high risk and 6-12 months for stable patients, and track trends rather than single values.

Risk assessment, monitoring and patient education

Screen for known mitochondrial insults by asking about drug history, pesticide/herbicide exposure, recurrent heat/stress events and family history; if serum lactate persistently exceeds ~2 mmol/L or CK is elevated, escalate testing and consider cardiology/audiology referral; educate patients to stop smoking, limit alcohol, correct vitamin D/B12 deficiency, and keep an activity plan with graded exercise and sleep hygiene to reduce cumulative mitochondrial stress.

Evidence-based therapeutic choices and safety considerations

Prioritize interventions with clinical evidence: CoQ10 (typically 100-300 mg/day) and riboflavin (100-400 mg/day) show benefit in subsets, L‑carnitine for documented deficiency, and idebenone (900 mg/day) for LHON; avoid valproate when POLG mutation is suspected; monitor LFTs, renal function and CK at baseline and every 3-6 months when starting supplements or drugs with mitochondrial toxicity.

Clinical evidence varies: randomized trials support idebenone in LHON and small trials/series support CoQ10 and riboflavin in some complex I/IV defects, while L‑arginine (e.g., IV bolus 0.5 g/kg) is used in MELAS stroke‑like episodes per case series; tailor dosing to weight, check interactions (statins with CoQ10), and stop or dose‑reduce agents linked to mitochondrial harm if labs or function worsen.

Indications for specialist referral and genetic testing

Refer to a mitochondrial or neuromuscular center if you see multisystem involvement (neurologic + cardiomyopathy, hearing loss, diabetes), early onset disease, progressive external ophthalmoplegia, recurrent stroke‑like episodes, persistent lactic acidosis, or strong maternal/family history; involve genetic counseling early to plan testing, reproductive options, and cascade family screening.

Order combined mtDNA sequencing plus an NGS nuclear gene panel (many labs cover >200-300 genes) as first‑line; use urine epithelial cells or muscle if blood heteroplasmy is low; expect panel turnaround 4-12 weeks (rapid WGS 7-14 days for neonatal crises); consider muscle biopsy only when genetic tests are nondiagnostic and clinical suspicion remains high.

Final Words

To wrap up, knowing the nine stressors – oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, nutrient deficiencies, toxins, sedentary behavior, poor sleep, psychological stress, excess sugar, and aging – helps you target lifestyle, dietary, and environmental changes to protect mitochondrial function and sustain your cellular energy over time.